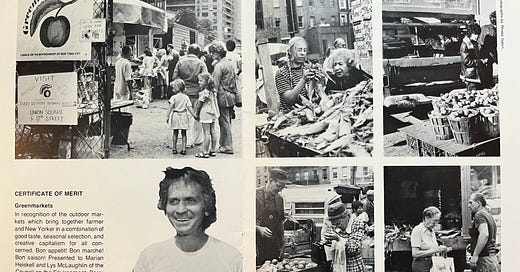

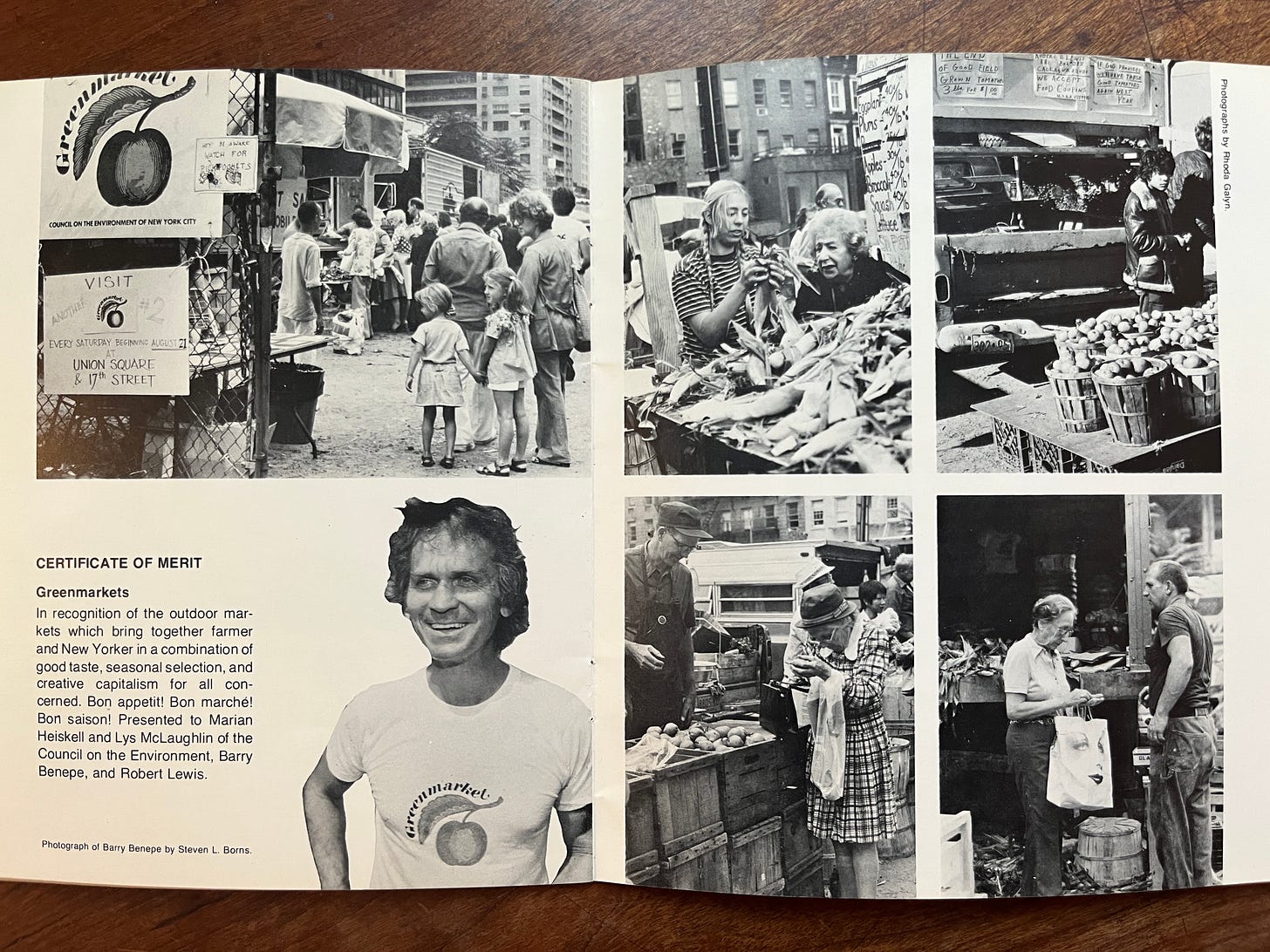

Barry Benepe, founder, New York City Greenmarkets

Issue 50: 1970s New York and the making of its farmers’ markets.

Why hello there! Welcome to on hand! If you’ve landed here and somehow aren’t subscribed, I got you:

New York City’s famers’ markets are such a fixture the city’s landscape, it’s hard to imagine a time without them. Today, there are 50 markets across all five boroughs, and you can find a market open on every day of the week.

This flourishing network is largely thanks to the work of Barry Benepe, a man, who in his 94 years, seems to have lived one thousand lifetimes. Barry worked with a small team to found the Greenmarkets in the mid-70s — a time in New York that is usually described as gritty, dark, and desperate.

I joined Barry in his walk-up in the West Village to talk about his background in city planning, his work with the Greenmarkets, and the role the markets play in a continually changing New York.

Brianna: Can you tell me about your background?

Barry Benepe: Well, I've always been a planner and planner consultant. First, I graduated in fine arts in 1950. The head of my department there set me up for a job at The Taft School, to teach art. I told him I didn't think I knew enough to teach it, and I wanted to go on to art school. So he recommended Cooper Union. At Cooper, it didn't give degrees yet, but I took a three-year course and got a certificate.

I was moving more from architecture into planning, gradually, because I wanted to embrace a larger context — socially and physically — whereas architecture was somewhat limiting. And even at Cooper, when we had a group project, I would usually be the coordinator and site planner, where others would do the individual buildings. So I evolved into planning. I wanted a degree in planning and MIT was recommended to me. I applied and was accepted, and I got my degree in architecture at MIT.

While there, I moved more into planning circles and planning jobs, first with planning consultants, and then with planning agencies. I was the chief planner for Newburgh, New York. I was also a planning officer in Newcastle, England.

In 1966, I wrote a piece for ENO Traffic Quarterly called Pedestrian in the City. The thrust of my argument was that planners had always planned for automobiles, but not for people on foot, and that we should plan for people on foot.

I drew examples in my article from Manhattan, and showed how we could interrelate. We look for generators of the traffic. Things like subway stations and bus stops, and then other destinations such as schools and hospitals and shopping and bus stops. And then look at the urban environment: the empty lots, the sides of buildings, the potential pass-throughs from street to street. These spaces are on a different scale than what automobiles use, so I could identify basically the hardware of the city, which would help pedestrians move more efficiently and pleasurably. That was the idea. So that was the emphasis I took as I evolved my planning thinking.

Brianna: How did your experience help with launching the Greenmarkets?

Barry Benepe: Well, I was quite active in the American Institute of Architects, and one of my mentors there was Robert Weinberg, a city planner and architect. He had a radio program on WNYC and would talk about planning. I asked if I could write one of his programs. I did, and they temporarily took him off the air because I criticized what the city was doing with Bryant Park and turning it over to development.

That got straightened out and he eventually hired me to work for his firm, which was a Canadian-based planning firm called Hancock, Little, Calvert Associates. He hired me because he wanted a planner who could work in rural areas.

Robert died, and I took over that office under Hancock, Little, Calvert Associates, but then started my own firm. I had no staff except for a secretary. Some of my clients included community boards in Manhattan. I was hired by Community Board 12 on the Upper West Side where I evaluated the impact of the West Side Highway on Harlem. I was also hired for Community Board 5 to look at the impact of urban plazas downtown and how they could benefit people in the city.

I eventually hired a man named Bob Lewis for two reasons. One, he had a background on working for Walter McCard in Pennsylvania. And McCard was notable for regional planning and including the regions around cities in his perception of planning. And I liked that background. He also had a foothold in Woodstock, New York. And I wanted to get work there, which I eventually did.

When I hired Bob, we were concerned about the loss of farmland to development. We contacted a private agency which was concerned with farmland loss, and asked them for funding, which they gave us to go out and develop a planning guide, which we did together.

We thought that we really had to address the issue at the ground-level: In order to keep farmers farming, they have to make money at what they do. So, rather than dealing with this as a land use issue, we dealt with it as an economic issue.

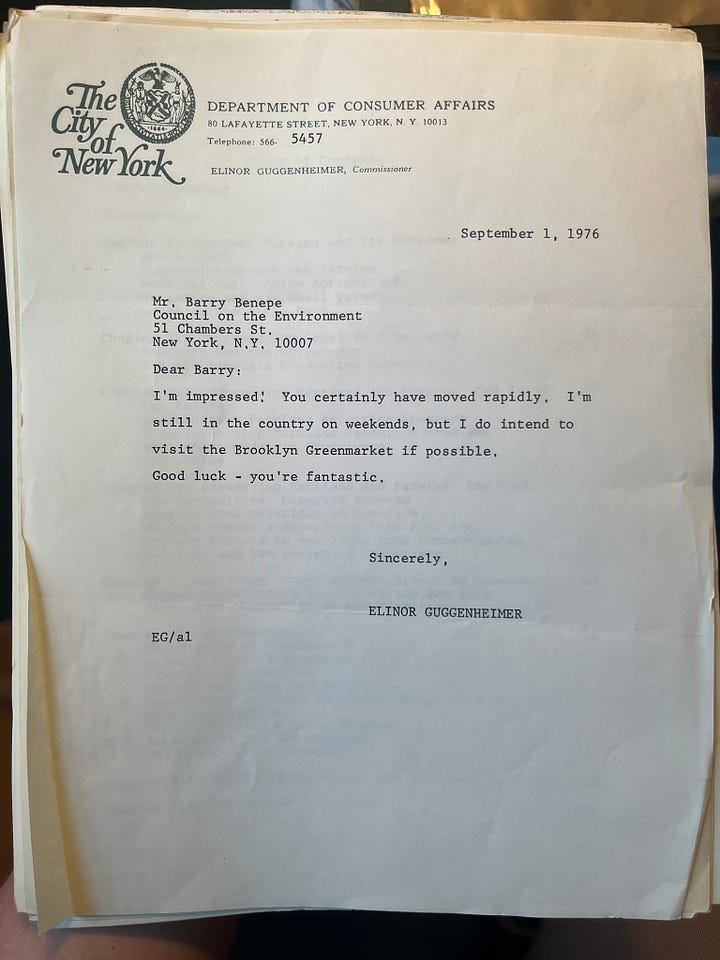

And so then, we developed the concept of the Greenmarket and we wanted to do a feasibility study for the city to run farmers’ markets. The city responded by saying they didn't have the ability to do it — that we should find a private agency. So we found the Council on the Environment in New York City, and I drew up a one page contract with the agency to start a program called Greenmarket.

We gave Greenmarket a service market protection. It's like a trademark, so nobody else could use the word. We actually stopped other people from using the word Greenmarket — we would've used farmers’ market, but anybody could use farmers’ market when there wouldn't have been a farmer within a hundred miles. I had checked with a law department in New York, "Can you enforce the term farmer's market to mean farmers?" They said they couldn't.

So that's how we developed Greenmarket to be a genuine farmers’ market. It became important to identify the word Greenmarket with farmers and farms. So then we pursued it through the Environment Council and I signed a one page agreement with them that made me director and I would raise the money. I went out to the foundations, and our chief funder at that time was the JM Kaplan fund. Their founder was the founder of Welch's Grape Juice, which is interesting.

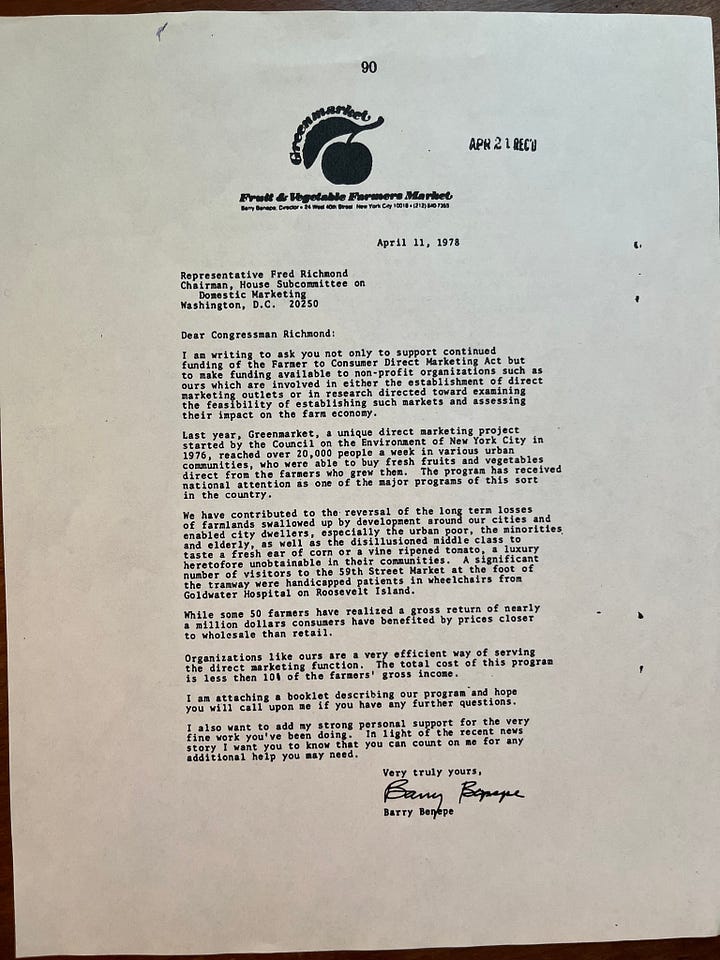

Our first grant was $800, but we needed to go out and raise serious money. We set this budget up for doing a feasibility study for the city to run a farmers’ market. And the foundations we talked to, the funders, said the city isn't capable of tying its own shoes, much less running a farmers’ market. So we had to find a private agency to do it and that’s where the Council on the Environment came in. It was perfect because it was made up of two agencies, which meant we could work with city agencies and private corporations, which helped us raise money. And that's when I moved into fundraising and proposal writing, and actually running markets. And that's when we got started: 1976.

Brianna: What made you think that the 70s were the time to bring this concept to New York?

Barry Benepe: It was the outgoing Lindsay administration, and I actually had worked on the campaign and he was a very forward thinker.

And I was very much a pedestrian advocate, so I worked on those issues with the Lindsay administration and Jay Kriegel who worked for him then. At that time I was trying to improve night lighting to make the streets feel more friendly at night by developing different kinds of luminaries. Going back to the mid 60s, I was working on two inter-related things: One is, I wrote the piece with Traffic Quarterly called Pedestrian City. And I also initiated the closing of the Central Park drives to automobile traffic.

I did it by organizing bicycle demonstrations. Once a year, the city closed the drives and had a bike race. We would tag in on the back of the race and keep the roads closed for incoming traffic for longer. We put our congressman in an electric vehicle to show environmentally-appropriate travel.

We did air quality measurements around the races and found that there were enormous improvements. And this was all publicized in the New York Times. We first began by asking for the drives to be closed every Sunday. My demonstrators each wore a letter in their back which spelled out Sunday Car Ban, but they got all mixed up and misspelled it. The people I organized with later became Transportation Alternatives.

You asked how that led to Greenmarket and I mentioned the Lindsay administration. There was generally an urge to make cities more livable for people on foot. Traffic manuals at that time actually regarded pedestrians as impediments to drivers, not for people to be considered as users of the road.

This was followed many years later by the governor's adoption of the Complete Streets Project Program. That program stated that streets were to be used by cars, pedestrians, and cyclists equally.

Brianna: How did you get farmers on board with this project and get them to come to the city?

Barry Benepe: Bob and I divided up our efforts. He went for farmers and I went for sponsors and funding. And you said it, the farmers didn't want to come into the city. They didn't trust the city — they thought they would come in with lots of produce, and go home with empty pockets. That they would be robbed at the gates by the mob. That the city was largely run by gangsters who would take their money.

Bob convinced them that it would be safe. Our main reach-out to farmers was through extension agencies, that were cooperative extension agents run through the counties. The agents gave us lists of farmers who were looking for urban markets for either direct sales, their own farm stands, or other ways of selling in the city. Bob reached to try to get the farmers to come in and try our market.

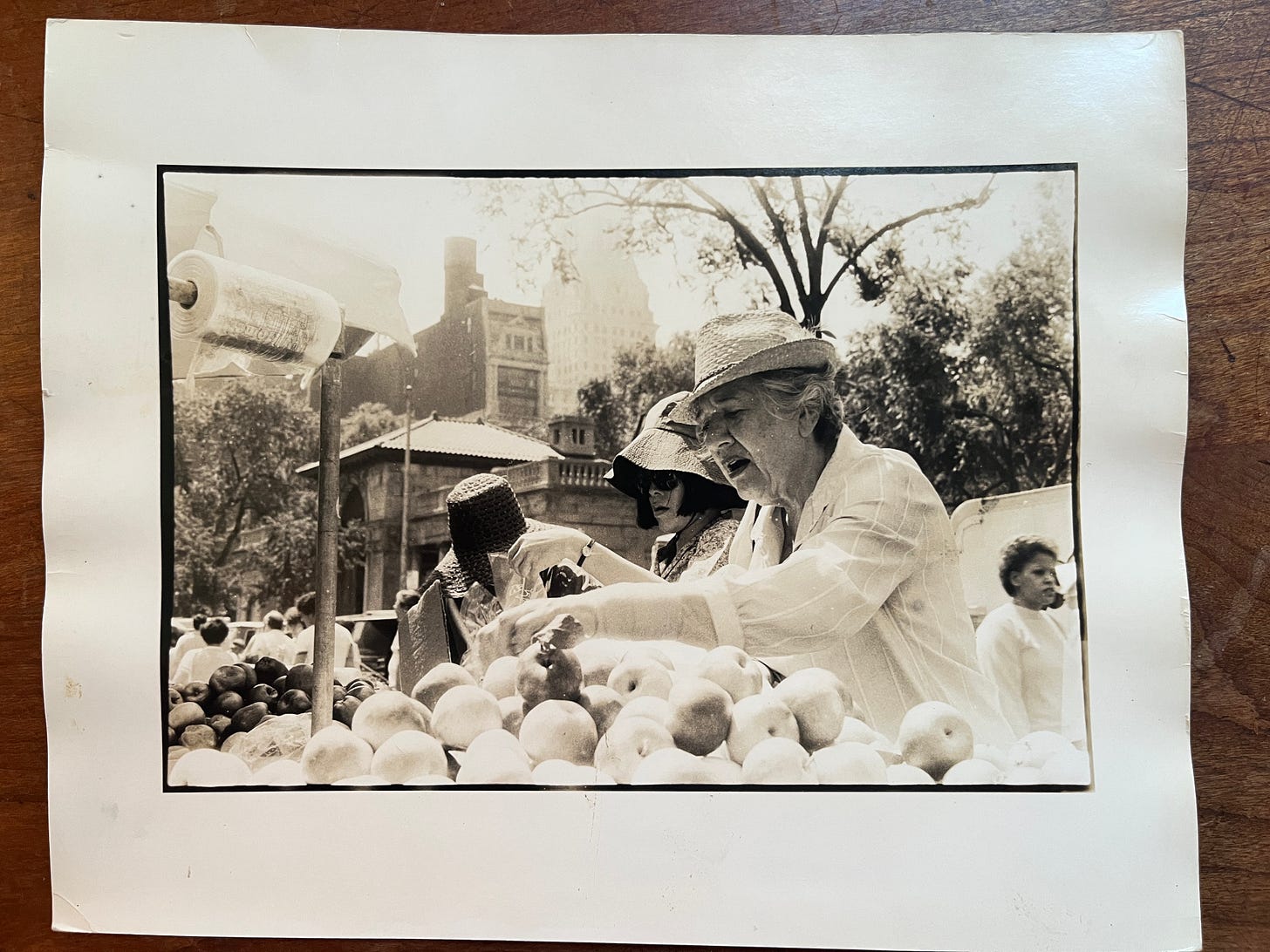

Our very first market was at 59th Street and Second Avenue. It was there because one of our funders had an executive director who had an empty lot near her house and wanted a market there. It turned out that the lot was used by the police on Saturdays to park their vehicles under a contract agreement that gave the police the a right to use any unused public spaces to park their private cars. Eventually the Police Benevolent Association actually voted to give us the lot on Saturdays.

If you remember the term location, location, location — it could not have been a better location. We were halfway between Bloomingdale's and Alexander's. We were in the passage between the two, so you had to stop. We had a lot of pedestrian traffic going by that lot, so all we had to do was hang a sign. It was gated with a chain link fence, so we could keep it closed at night.

I was responsible for publicity. I put out flyers. I sent out a press release and the press picked it up right away. They loved the idea. So they came to our opening day and made it a news item. At the end of the news, they had a piece about Greenmarket. So the whole city knew about us. It was just so great that things pulled together.

Brianna: How did you leverage that publicity and interest into launching more markets across the city?

Barry Benepe: When we started at 59th Street and had a huge amount of publicity, private groups all over the city were calling us, "Can you bring a market to our area?" And we would never consider it until their community board supported us. We had a local sponsor, a woman named Minerva Coleman, and she wanted one on her block. She was ideal for us because she had an ongoing agency with deep roots in the community, people who knew her and respected her. And so, when she got behind the market being on her block, we were able to bring them to more neighborhoods.

Brianna: What role did you see the market playing in a changing city in the seventies?

Barry Benepe: One of the market's main roles is the transformation of urban space. The reason we came to Union Square was because we were contacted by the head of the planning office. Nobody came to the market for the first few weeks, it was considered a crime infested area.

But the reason we went to Union Squares is because the city planning department asked us to go there. The head of the Manhattan office heard about us on the radio and she asked us if we would consider Union Square. We did it in collaboration with other groups because, at that time, many people were considering moving to Union Square into the empty lofts. At that time, the Union Square Community Coalition was born, headed up by people who lived in the lofts.